Monday, September 23, 2019

Power: Atomic Power

Uncle Tupelo: Atomic Power

[purchase]

This is going to be one of those posts that tries to create a fusion of different things. Let’s see if it works, or if it turns out to be like “cold fusion.”

Remarkably, although I’ve mentioned them in writing about Jeff Tweedy, Jay Farrar, and Wilco, I’ve never written a post on this site about Uncle Tupelo (although I did a long one at Cover Me). I wasn’t aware of the band during their existence, and learned about them after discovering Wilco and Son Volt, the two bands that were formed when childhood friends Tweedy and Farrar could no longer coexist. I wrote in detail about Uncle Tupelo’s history in that Cover Me piece, so, if you are really interested, go check it out, and come back here when you are ready.

R.E.M.’s Peter Buck heard Uncle Tupelo perform a cover of the Louvin Brothers’ song “Great Atomic Power” at a concert, and contacted the band after the show. The three musicians found a great deal of overlap in their musical interests, including bluegrass, and decided to do an acoustic project together. The band’s prior album, Still Feel Gone was, for the most part, a rocker, so it was a bit of a risk to follow it up with an acoustic album, and their record company was pressuring them to move to an even more rock-oriented sound, to compete with the emerging grunge movement. But Farrar and Tweedy were, as always, headstrong, and pissed at their label’s failure to pay them royalties, so they must have figured, “Fuck it,” we’re going to work with Peter Buck, and do an acoustic album.

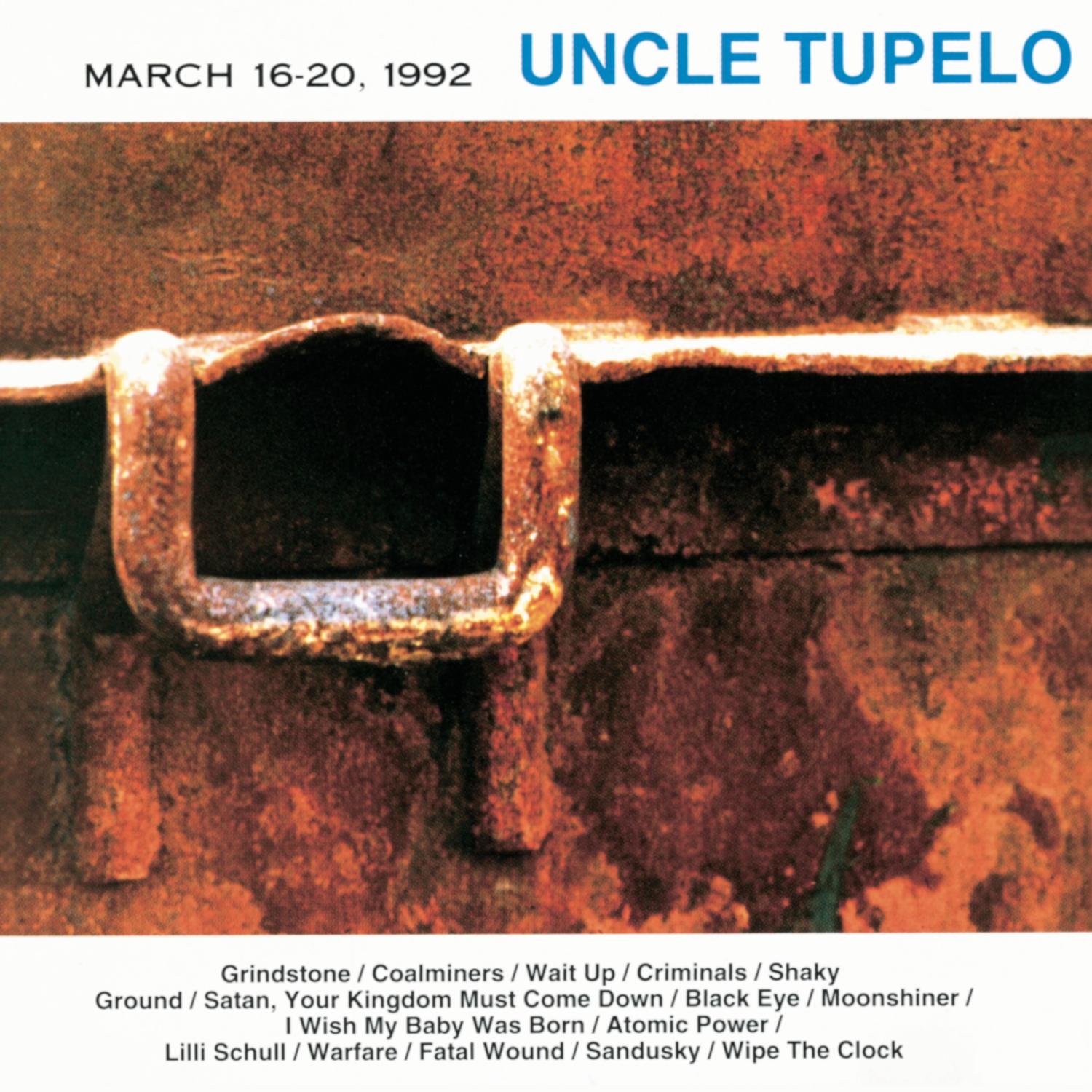

That album, March 16–20, 1992, mixed classic country tunes with originals that fit seamlessly with the older songs. Roadie Brian Henneman, who later founded the Bottle Rockets, even got to play the mandolin that was used in “Losing My Religion.” Uncle Tupelo’s cover of “Great Atomic Power” is very faithful to the Louvin Brothers’ original, and it is a very, very odd song.

It mixes the imagery of a devastating nuclear explosion with Armageddon, and asks the question—when that horrible time comes, will you be ready to meet your savior? As the lyrics inform us:

There is one way to escape and be prepared to meet the Lord

Give your heart and soul to Jesus,

He will be your shield and sword

He will surely stand beside and you'll never taste of death

For your soul will fly to safety and eternal peace and rest

The Louvin Brothers, Ira and Charlie, were popular in the 1950s and 1960s, and came from the gospel tradition, as many country singers did, so the fire and brimstone is not all that surprising. Charlie seemed to be the stable brother, while Ira was an alcoholic, who engaged in erratic and often abusive behavior, including toward his brother. Ira was married four times, and wife number three shot him four times in the chest and twice in the hand after he allegedly tried to strangle her with a telephone cord. Ira once made a racist remark that so angered Elvis Presley that Elvis refused to record any Louvin Brothers’ songs, probably costing the duo significant royalties.

Ultimately, Charlie had enough, and the brother act broke up in favor of separate solo careers. Ira and wife number four died in a car accident in 1965, when a drunk driver hit their car; Charlie lived until 2011, and recorded and performed until close to the end.

The Louvin Brothers make a brief appearance in Episode 4 of the Ken Burns documentary, Country Music, before the documentary moves on to a more popular act, The Everly Brothers, which is ironic because a suggestion that the Louvins change their sound to be more like the Everlys reportedly depressed Ira and contributed to his alcoholism.

As I write this, I’ve watched four episodes of Country Music and am enjoying it immensely. I really know little about the history of country music—it was not something that I listened to growing up in the NY suburbs. Like the blues, much of my knowledge of the genre has come from listening to covers, like “Atomic Power,” and going back to listen to the originals. And as I have become increasingly interested in Americana music, I find myself more interested in the music’s roots.

I’m someone who finds how things start to be fascinating, so it has been interesting learning about the long background and history of country music. One of the things that I have found striking is that even in its earliest days—going back to the 19th century—one of the hallmarks of country music has been nostalgia for older, simpler times. And I get that, although it often seems that there’s a real fear of trying anything new and radical. Which is why Elvis Presley, who came from a country and gospel tradition clearly scared the crap out of, and was rejected by, the establishment. And it is interesting, too, that when the Louvin Brothers, who were traditionalists, chose to write “Great Atomic Power,” about something new and scary, rather than write about the potential of the new technology, they (and co-writer Buddy Bain, a musician and DJ) focused instead on its destructive power, and tied it to traditional religion.

For what it is worth, what made Uncle Tupelo stand out from the crowd was the way that they fused the tradition of old time country music with the new energy of punk, so it is also interesting that March 16–20, 1992 sounds so traditional. It is a bit of an oversimplification, but as time went on, it seems like Farrar (and Son Volt) has more often followed the country tradition of looking backwards, while Tweedy (and Wilco), have tended to look forward, including more rock and experimental influences in their music.

Of course, the potential of atomic power was touted by many, and numerous nuclear plants were built in the US and elsewhere, because of the desire to move away from depleting and polluting fossil fuels, until, at least in this country, the tide turned against them due to the danger of accidents and the difficulty in safely storing the radioactive waste. However, there seems to be some attempt to revive the industry, as it becomes clear that use of carbon based fuel continues to damage the environment, although its serious risks continue to be an obstacle.

The risks, of course, are real, as Chernobyl and Fukushima, among others, remind us. And I recall, that during my sophomore year in college, one of my roommate's friends stayed with us when his college was closed because of the partial nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island. A few years later, when I was a very junior associate at a very large Wall Street law firm, I was mostly working on two cases. One was the representation of Drexel Burnham, in the various investigations arising from the Mike Milken/junk bond issues. The other was representing Public Service of New Hampshire in proceedings to determine whether the costs involved in constructing the Seabrook nuclear power plant were reasonable, and could thus be passed along to the ratepayers. For the first one, much of my work revolved around gathering and reviewing Drexel Burnham documents to see whether they were responsive to an ever growing number of government subpoenas. The second one had me and a slightly more senior lawyer traveling regularly to Philadelphia to prepare our clients and monitor extremely dull hearings about arcane engineering issues.

Neither of these were particularly interesting, and I did have some qualms about representing a nuclear plant, but that’s the way it goes as a young lawyer at big firms. One day, though, the senior partner on the Drexel case offered me the opportunity to spend a week (with other lawyers) at Drexel’s office in Beverly Hills. This was during the winter in New York, so it seemed like it would be fun. And, in those days, we all flew first class and stayed in fancy hotels. I was excited. Shortly after that, the senior partner on the Seabrook case offered me the opportunity to spend the same week in the small town in New Hampshire where the plant was, doing work in a makeshift office on the construction site. I, not at all regretfully, told him that I couldn’t, because I was going to Beverly Hills. A little while later, I got a call informing me that I was going to fly to California, spend half the week there, then take a redeye to Boston and drive to Seabrook. I will never forget that one day, I was staying at the Biltmore Hotel in Beverly Hills and walking around Rodeo Drive in warm weather and the next day I was tramping through the mud in the cold, and staying at the Hampton Falls Inn, a motel near the plant. At that point, I was no fan of atomic power, great or not.

blog comments powered by Disqus